Over the past two summers Russell Library interns Ashton Ellett and Kaylynn Washnock assisted in curating the new exhibit, “Food, Power, and Politics: The Story of School Lunch” opening September 26th in the Russell Library’s Harrison Feature Gallery. The exhibit examines the complicated past of the National School Lunch Program, from feeding malnourished children and putting excess commodities to good use, to the more recent debates over childhood obesity and nutrition in America. This post is one in a series where Ashton and Kaylynn provide a preview of key documents featured in the exhibition.

At the end of World War II, proponents of ongoing school lunch programs worried that the federal government’s ad hoc, hand-to-mouth funding scheme discouraged local school districts from participating. Many districts were reluctant to invest scarce funds into capital intensive projects like cafeteria construction and kitchen equipment purchases without guaranteed federal funding.

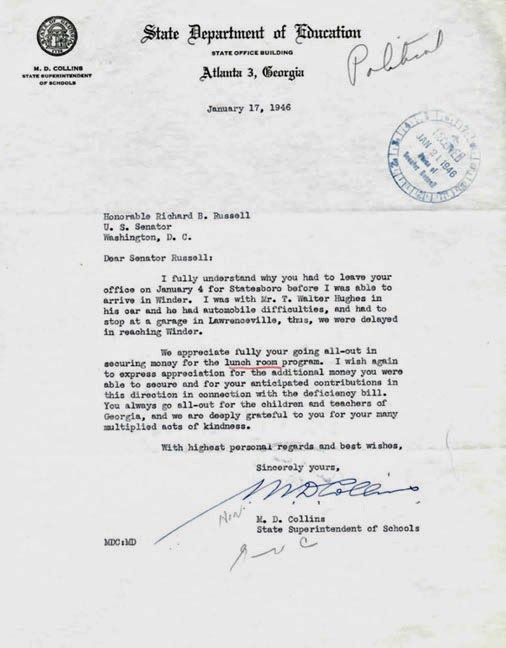

Despite a fierce legislative battle over the responsibilities of parents and the role of schools, President Truman signed the National School Lunch Act on June 4, 1946. The passage of the bill was due in large part to the lobbying of a select group of politicians—including Georgia Senator Richard B. Russell. A letter from Dr. Mauney Douglas Collins, State Superintendent of Schools, dated January 17, 1946, to Senator Russell demonstrates the widespread appreciation among education officials in Georgia for his support of the legislation.

A letter from Bob Shields (pages 1-3 below), administrator of the USDA’s Production and Marketing Administration, to Russell in June 1946 stresses the historical importance of the newly passed national school lunch program, which he saw as both a challenge and an opportunity. In his speech before Product and Marketing Administrators, Shields indicated the legislation marked “a new era in farmer-consumer relationship” and reaffirmed the program as “a measure of national security.” During World War II, Major General Lewis B. Hershey, director of the Selective Service System, testified before the House Committee on Agriculture that many young men were rejected for military service because of nutritional deficiencies. With the nation at war and the memory of farmers suffering during the Great Depression at the forefront of many minds, how could the nation’s nutrition and farm problems be solved? The original legislation intended to serve as both a childhood nutrition and surplus commodity program. Since 1946, the U.S. government has been involved in both the “production and marketing” of food because of, according to Shields, the “humanitarian vision and constructive statesmanship.”

Want to find out more about School Lunch? Visit Food, Power, and Politics: The Story of School Lunch on display in the Harrison Feature Gallery of the Special Collections Building from September 26, 2014 through May 15, 2015. The Russell Library gallery is free and open to the public weekdays from 8 a.m.-5 p.m. and on Saturdays from 1-5 p.m. For more information, email russlib@uga.edu or call 706-542-5788.

At the end of World War II, proponents of ongoing school lunch programs worried that the federal government’s ad hoc, hand-to-mouth funding scheme discouraged local school districts from participating. Many districts were reluctant to invest scarce funds into capital intensive projects like cafeteria construction and kitchen equipment purchases without guaranteed federal funding.

|

| Letter from M.D. Collins to Richard B. Russell January 17, 1946. Richard B. Russell, Jr. Collection, Russell Library. |

A letter from Bob Shields (pages 1-3 below), administrator of the USDA’s Production and Marketing Administration, to Russell in June 1946 stresses the historical importance of the newly passed national school lunch program, which he saw as both a challenge and an opportunity. In his speech before Product and Marketing Administrators, Shields indicated the legislation marked “a new era in farmer-consumer relationship” and reaffirmed the program as “a measure of national security.” During World War II, Major General Lewis B. Hershey, director of the Selective Service System, testified before the House Committee on Agriculture that many young men were rejected for military service because of nutritional deficiencies. With the nation at war and the memory of farmers suffering during the Great Depression at the forefront of many minds, how could the nation’s nutrition and farm problems be solved? The original legislation intended to serve as both a childhood nutrition and surplus commodity program. Since 1946, the U.S. government has been involved in both the “production and marketing” of food because of, according to Shields, the “humanitarian vision and constructive statesmanship.”

In spite of lofty goals, the original National School Lunch Act lacked the legislative provisions and enforcement abilities to serve America’s neediest children. Reform and expansion of the program would come later from another war – one inspired by grassroots activism and social movements of the 1960s.

No comments:

Post a Comment